September 19, 2022

Biodiversity: Our Unsung Hero

What if I told you there was a miracle product that could cure physical diseases, improve your mental health, provide you with ongoing food and shelter, boost the general wellbeing of you, your family and your community, and more?

How much would you pay to access it?

What lengths would you go to to ensure you could keep accessing it?

The biodiversity of our environment (locally, regionally, nationally and globally) is just such a miracle product — yet like all unsung heroes, it doesn’t get the kudos or attention it deserves, and it needs our help.

What is Biodiversity Anyway?

Biodiversity (from biological diversity) refers to the full and total variety of living things in all their forms — the microscopic to the mega, flora to fauna — at any given time in our environment.

More than that, and intrinsically linked to the nature of biodiversity, is how all these living things interact (this is called an ecosystem). The inventory of varied and diverse living organisms that make up Earth’s biodiversity aren’t just sitting on a shelf waiting their turn. They’re bound into a complex, mind-blowing, interdependent dance in which all living organisms play their role.

We’ve got front row seats to this dance in Australia. According to the Australia State of the Environment 2016 report, around 150,000 species have been formally described in Australia but this is only about 25% of the total number present. Total organisms in Australia are likely to be closer to between 600,000 and 700,000, many of which are found nowhere else in the world. We’re also considered one of the world’s 17 megadiverse countries, which together account for 70% of the world’s biological diversity across less than 10% of the world’s surface.

What Makes Biodiversity a Hero?

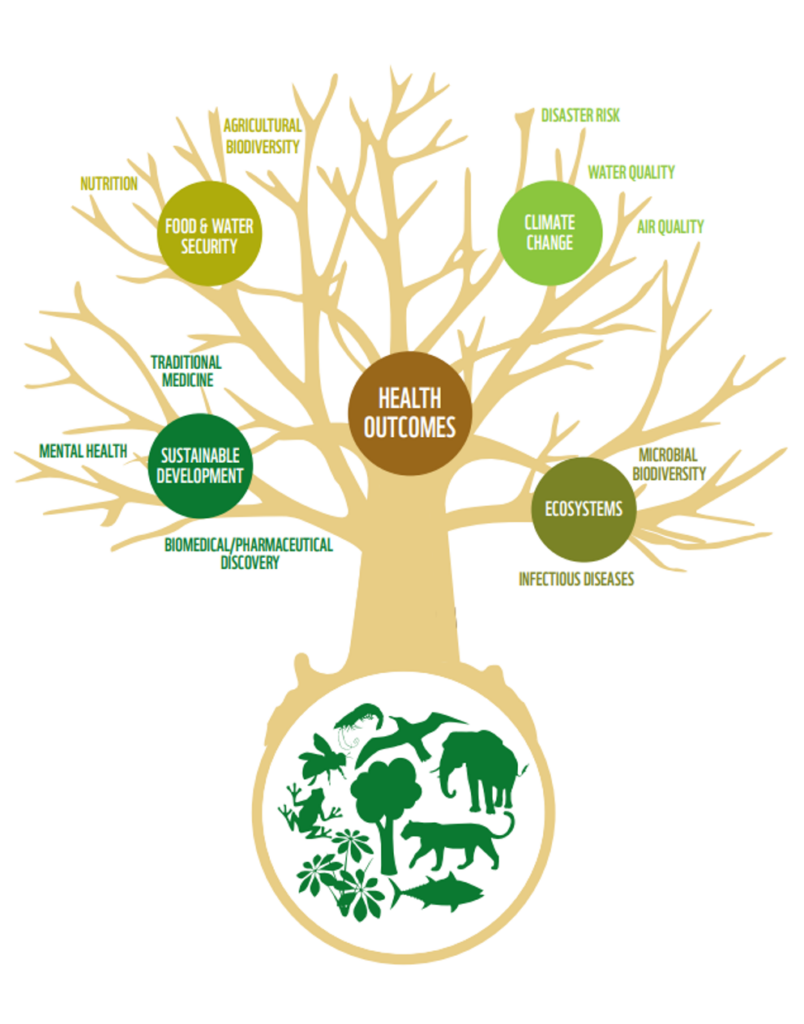

The most common way to summarise what a biodiverse environment does for us is to consider all the services the natural world provides (basically for free) that we often taken for granted. These are called ecosystem services.

According to the IUCN (the World Conservation Union), the monetary value of these ecosystem services is estimated to amount to some US$33 trillion per year. That is, if our ecosystem was no longer able to do what it does for free, we’d have to find an extra US$33 trillion ($33,000,000,000,000) in the global budget. And even then, we wouldn’t be able to replicate all the services.

Looking beyond the ledger, biodiversity also arguably has intrinsic value. That is, every species has value and a right to exist purely because it does exist — whether or not it is known to have value to humans.

But if you want to talk purely about human benefit, the ecosystem services our biodiverse natural systems provide can be broadly broken into four groups:

- Supporting services: these include vital system support processes including the cycling of nutrients, pollination, primary production of base and organic materials, the formation of soil and decomposition of organic matter.

- Provisioning services: these include the provision of vital resources including food, fresh water, wood and fibre, and the many medicines and therapeutic compounds that have been used to advance medical treatments across the world. More than 70,000 plant species are used in traditional and modern medicine, and 25–50% of all pharmaceutical materials are derived from genetic resources.

- Regulating services: Many supporting and provisioning services would be impossible without the range of regulating services our diverse ecosystems provide, including climate regulation, air quality, disease regulation, water purification and flood mitigation.

- Cultural services: beyond the physical provisions, the value of our ecosystems to our personal and community wellbeing cannot be ignored. Ecosystems and natural environments provide fundamental aesthetic, spiritual, educational, recreational and cultural services. Time spent in nature has been shown again and again to have wide-ranging physical, emotional and mental benefits, and the unique cultural and community identities and histories found across the globe are steeped in our ties to the natural world.

Like the unsung heroes of our stories, our biodiverse ecosystems provide these services and more, every minute of every day, without rest or payment.

What Happens When Biodiversity is Lost?

In short, ecosystems weakened by a loss of biodiversity are less likely to deliver these critical ecosystem services. The breakdown of any one ecosystem service (let alone more than one) would be devastating to human life on this planet. It’s not just about the big picture either — each individual species matters intrinsically and provides benefit. It has been recently discovered, for example, that skin secretions from the Green and Golden Bell Frog (found in Sydney’s Olympic Park among other places) are toxic to a range of bacteria, including multi-drug-resistant golden staph (MRSA), a serious infection that has, to date, proven difficult to treat and is deadly to humans. There is so much more to be learnt about the species we know of, and those we are yet to discover.

The Living Planet Report 2020, published by WWF, sadly revealed Earth has experienced a global species loss of more than two thirds in less than 50 years. The numbers of mammals, birds, fish, plants and insects have fallen an average of 68% from 1970 to 2016. So, things aren’t on a good trajectory.

Here in Australia, invasive plants acting as landscape-scale weeds are having a devastating impact on the biodiversity of our natural landscapes. More than 207 invasive plants impact 1,257 threatened and endangered species in Australia and the six most common weeds cover an area three times the size of Tasmania (20 million hectares), causing untold loss of local biodiversity and landscape resilience.

So, What Can We Do?

While there are many actions we must take to protect and regenerate the biodiversity of our natural landscapes here in Australia, there is one easy action that starts in our own backyard.

Seventy-two per cent of the invasive plants we’re battling in our bushland right now started as ornamental garden plants that were introduced for use in residential gardens and got out of control — and around 12 new ornamental plants establish themselves each year in native bushland and become naturalised.

Gardening Responsibly is a groundbreaking new program that harnesses the power of scientific research and multiple stakeholder collaboration to prevent future landscape-scale weed invasions by turning off the tap of invasive plants establishing in our natural landscapes.

We’re working with plant experts and researchers across the country to assess the 30,000 ornamental plants in trade and certify those with a low risk of “jumping the garden fence.” This allows plant growers and suppliers to prioritise low-risk plants, and gardeners to easily identify and choose plants that will look great in place — and stay in place. It’s a simple step that we can all take to help protect our megadiverse natural landscapes — and to ensure they remain the hero we all need.

Melissa Sellen

Melissa is an experienced writer, communicator, educator and strategic projects manager with over 20 years’ experience in corporate, government and not-for-profit organisations. She loves working with passionate people on complex and meaningful projects across a range of industries to improve project clarity, streamline project delivery and maximise project impact for the protection of our environment and improvement of our society.