September 3, 2022

Did Prickly Pear Cause the Extinction of the Paradise Parrot?

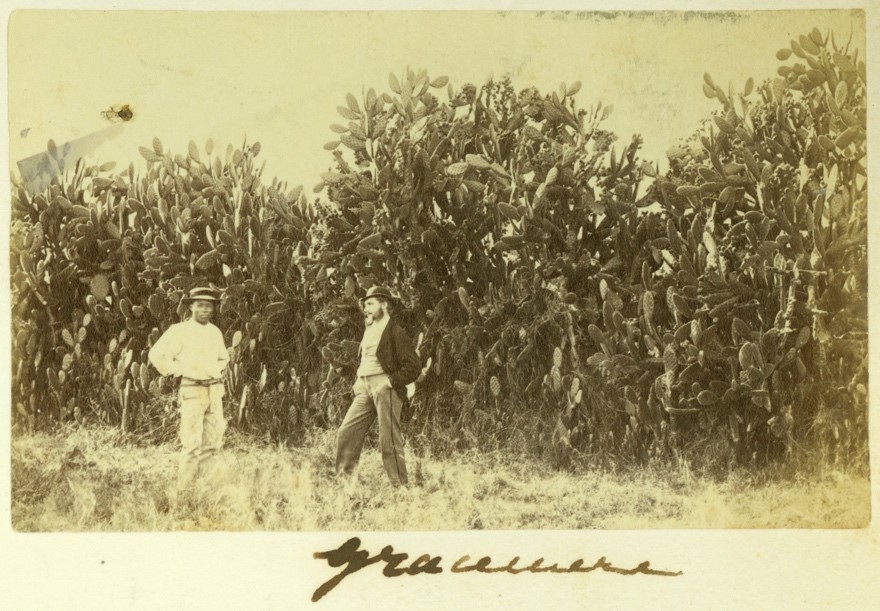

A century ago, Australia was under siege. Headlines screamed ‘Prickly Pear war declared,’ warning of a ‘silent invader.’ Couched in military terms, articles and silent films told the horrifying story of the ‘dreaded Prickly Pear,’ its ‘onward-march’ and the ‘battle’ to contain it. It all began innocently enough, another hundred years earlier.

In 1822, cuttings of Prickly Pear (Opuntia sp.) were brought to Australia and planted to make fences — a prickly barrier to livestock. Cuttings were shared, the plant self-spread and the seeds dispersed widely in the droppings of birds, livestock and other animals. Mid-century, more varieties of Opuntia were introduced as garden plants, hedges, fences and emergency drought feed for stock. In the final decades of the century, warning bells began to ring. The cactus’s spread was relentless and frantic attempts to control it by chemical and mechanical means failed.

By 1925 it is estimated to have invaded some 25 million hectares, extending from Mackay, Queensland, into northern New South Wales, smothering pastures and native plants, and driving countless farmers and graziers off their properties. The addition of a moth (Cactoblastis) to the armoury finally brought the invasion to an end in the 1930s. Formerly overrun land was returned to production, but what of the native plants and animals?

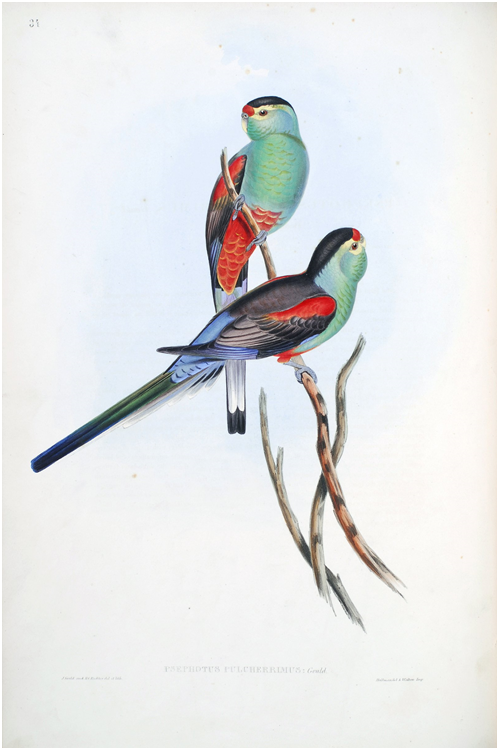

The Paradise Parrot (Psephotellus pulcherrimus), said to be one of Australia’s most beautiful parrots, once occurred in the grasslands and open woodlands of south-east Queensland, totally within the extent of the Prickly Pear invasion, including some of the worst affected areas. The last confirmed sightings of the bird were made in the 1920s, at the height of the cactus crisis. Cyril Jerrard, a farmer at Proston, Queensland, took photographs of a pair at their nest in a low termite mound and reported that he last saw the species in 1926.

State Library of Queensland

“…without exception the most beautiful of the whole tribe I have ever seen…”.

Jerrard was responding to calls by concerned ornithologists for records. The parrot was already vanishingly rare, probably due primarily to overgrazing of the seeding grasses on which it relied for food, exacerbated by removal of termite mounds for roads, tennis courts and the like, drought and other threats. By the late 1930s, the Paradise Parrot was almost certainly extinct. We will never know for sure, but Prickly Pear may well have been the final straw. Ironically, a moth helped bring the cactus under control, and it is thought that when the parrot disappeared so too did a symbiotic moth whose lifecycle was dependent on the droppings of the bird’s nestlings.

How much else was lost? Plants and animals gone forever, in part due to what seemed to be a harmless garden plant and livestock barrier. Prickly Pear infestations still occur, requiring constant vigilance. The Paradise Parrot was unique to Australia. It is the only mainland bird to have been driven to extinction in historical times — we don’t need to lose any more.

When people plant a garden, they believe they are doing something good for the environment and most of the time they are. Sometimes, however, the plants they choose can become invasive weeds, which can really hurt our native plants and animals.

When you garden responsibly, by choosing and recommending plants with the Certified Gardening Responsibly eco-label, you can be confident you’re doing your bit to secure beautiful gardens and healthy Australian landscapes, and to protect our native animals.

Dr Penny Olsen

Ornithologist and author

Dr Penny Olsen is an Honorary Professor in the Division of Ecology and Evolution in the Research School of Biology, Australian National University.

After a career as a field biologist and ecological consultant, she is now mostly occupied writing books about Australian natural history and its recorders, both artistic and scientific.

In 2011 she was invested as a Member of the Order of the Australia for her for ‘service to the conservation sciences through the study and documentation of Australian bird species and their history.’

Her most recent publications include Australia’s First Naturalists: Indigenous Peoples’ Contribution to Early Zoology, Flight of the Budgerigar: An Illustrated History and Feather and Brush: A History of Australian Bird Art.